Upmarket Epic Fantasy

While I Am Alive

When the Living Shadows, the imperial secret police, catch Surrie elbow-deep in the belly of a poached deer, she knows she has just two options:

Run, or hang from the maypole at dawn.

Except Surrie didn't mean to run to the frontlines of civil war, where the ragtag revolutionaries of the Rising fight to bring bread and medicine to the downtrodden masses. As if being caught up in a war that isn’t hers isn’t enough, she’s soon misidentified as the daughter of a beloved folk hero with enough support to threaten the imperial status quo — making her too valuable for the Rising to lose, and too dangerous for the Living Shadows to let live.

To stay in the Rising's good graces and out of the Living Shadows' clutches, Surrie reluctantly impersonates the legendary folk family, risking life and limb to destabilize the Living Shadows as the bounty on her head grows. So much for starting over with a clean slate – but she’ll get her hands dirty if it means destroying the Living Shadows who made her life hell.

Yet all is not as it seems in the Rising. Bigoted rebel generals with personalities like pit vipers promise to make Surrie a martyr not if but when she fails, and as her missions get harder – and more morally grey – she realizes the enemy is manipulating the Rising from within, sabotaging them — and her — from the inside out.

One mistake from martyrdom and two steps from capture by secret police, Surrie will have to trust dangerous allies, make allies of untrustworthy strangers, and befriend outsiders even stranger than she is to unravel the Living Shadows’ plot, outfox corrupt generals, and win the right to a peaceful life. But as the fighting intensifies and the lines between Living Shadow and Rising blur, Surrie’s actions will lead her to the festering heart of the Linnean Empire itself – with fatal consequences.

Surrie will take you on a tour de force through the machinations of a morally bankrupt authoritarian regime and the tenacious resistance that might, in some respects, be even worse (for her). In a world without magic, she has to rely on herself, and the precious few people she can trust — if she can find them. As for Surrie, if she makes it another day without the Living Shadows or Rising sticking a knife between her ribs, it’s a win. But as self-centered as she is — as much as she wants to keep living — there might just be some people worth dying for.

Readers should expect a lush, grounded secondary world with fully-realized political systems, cultures, and histories, each region peopled by allies and adversaries who stop at nothing to get what they want. Found family is a very strong theme throughout the story, and while there is a romantic subplot (friends-to-enemies-to-lovers), it’s secondary. There is no “chosen one,” at least, not one chosen because of birthright or the luck of natural talent. In the Linnean Empire, there are no shortcuts to survival. WHILE I AM ALIVE is complete at roughly 200,000 words and was designed to be the first of a series, though it can be modified to stand alone.

I am actively querying this project. Wish me luck! In the meantime, read the first three pages below!

The grittiness of The Poppy War meets tyranny of Mistborn in the broken world of Breath of the Wild.

Other comparable titles include…

THE WILL OF THE MANY

James Islington

SWORDCROSSED

Freya Marske

PRIORY OF THE ORANGE TREE

Samantha Shannon

GIDEON THE NINTH

by Tamsyn Muir

THE SUN AND THE VOID

Gabriella Lacruz

SHE WHO BECAME THE SUN

Shelly Parker-Chan

What beta readers are saying

Read the first chapter here!

WHILE I AM ALIVE

ACT I

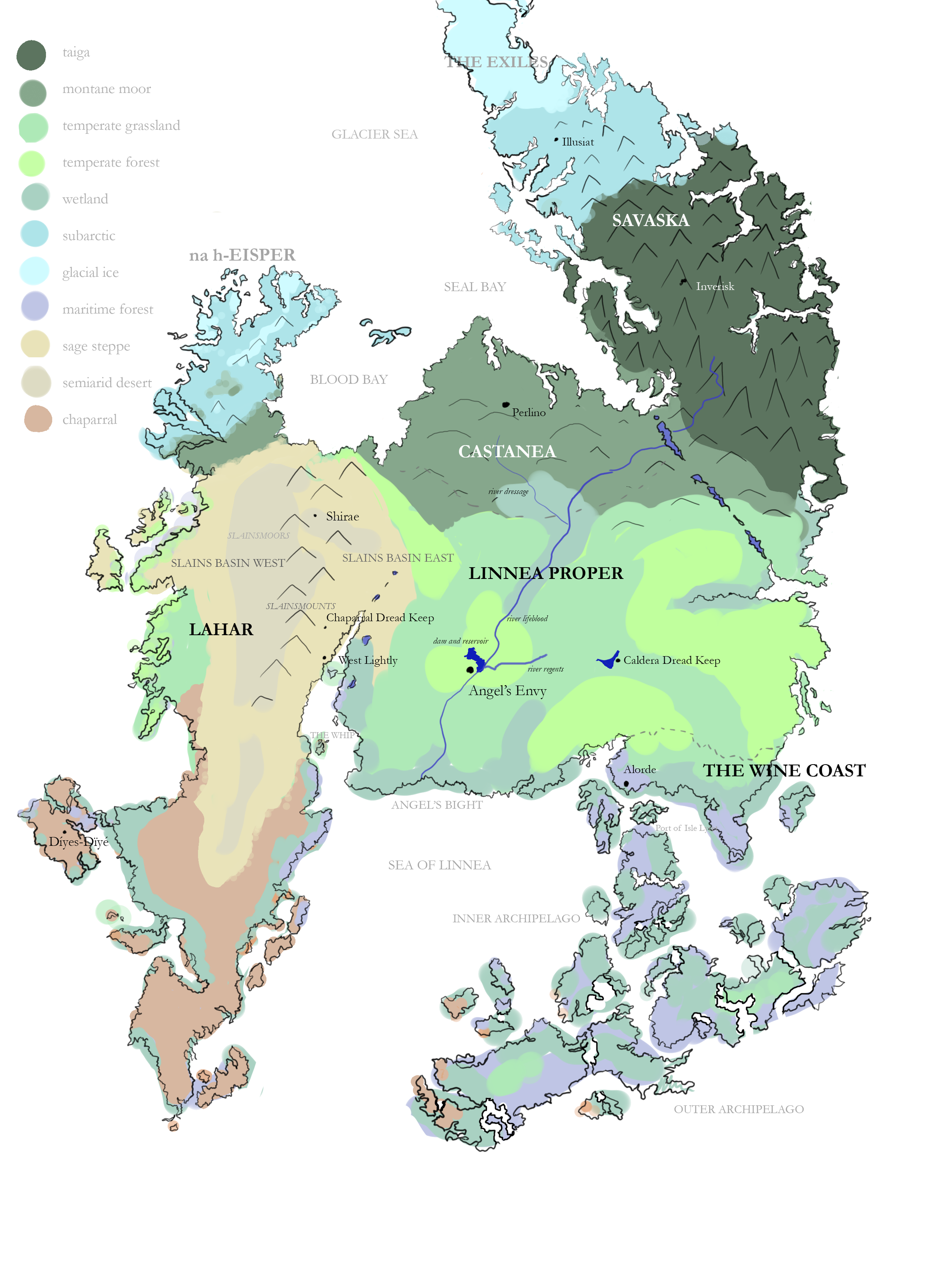

ONE / SAVASKA

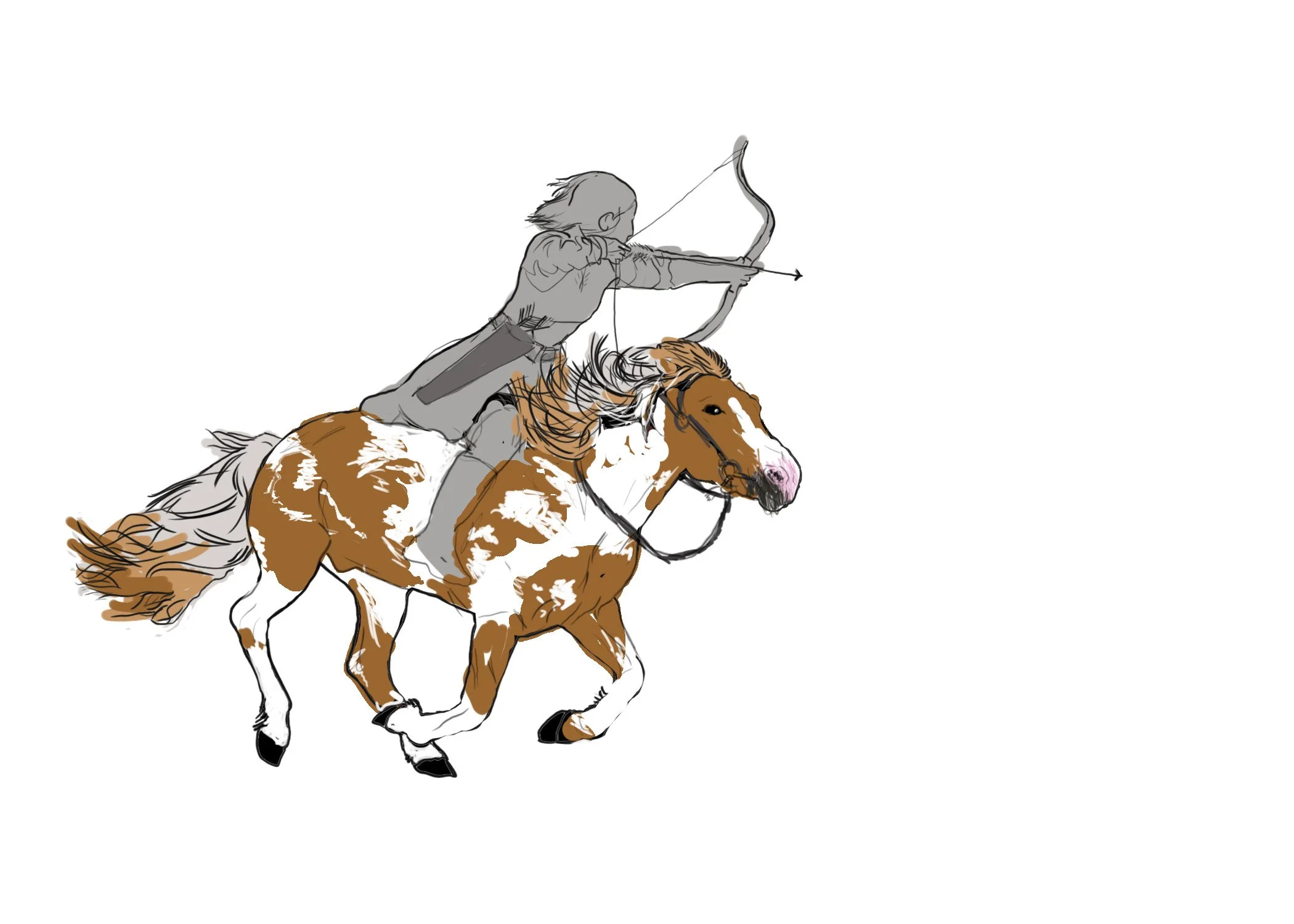

She was condemned from the start to die, that doe, hunted alone in the cold. The fatal arrow skewered her heart like a needle through cloth, beads of hot blood splattering the snow like paint on a blank canvas. Dizzy with relief, hardly breathing, Surrie of Inverisk lowered her bow. She prayed for the doe’s forgiveness—for its swift and painless end—but she did not apologize.

It was always this way. The adrenaline of the shot, the gutting dread of missing, the drunk ecstasy when she aimed true. That doe, that lovely, scrawny, red-brown beauty staggering into the woods to bleed out and die, was the first deer Surrie had glimpsed in three moon cycles. By the wolf spirit, by the borealis, let the doe be quickly dead, Surrie prayed, eyes closing.

It was spring in the heights of Savaska. The creak of cracking ice boomed across the mountains as the rivers shook off their icy shackles, and in the woods festooned in snow, the first patches of black soil soaked with snowmelt had appeared. Surrie’s provisions of smoked salmon had run out two moons ago, and the elk meat had been taken for tax the morning of the early snow the moon earlier. Pangs of hunger had pierced her stomach ever since the Storytelling Moon, and the past fortnight had seen her eat little more than boiled bark and broth rendered from mouse bones.

Surrie spied the deer’s blood trail with desperate, almost delirious hope. In better times she would have spent the bitter thaw curled up before the hearth, grinding paint pigments from leaves and pestering her only friend and confidant, Rowan, to give her a crack at carving a hunting bow from the pillar of yew wood. She was more than good enough to warrant a try, if the children squabbling over the little carved animals she hid throughout the village were anything to judge by. She was at heart an artist, a craftswoman, who saw Savaska and all its vivacity in oil paints and watercolor, who felt the immediacy and ecstasy and violence of life like hot breath against her neck on a cold morning. The full-bodied curve of ivory antlers, the thick rugged ruff of hispid hairs arrayed across a wolf’s throat—she could have devoted her life to committing those scenes to ink and watercolor, chiseling lifelike little creatures for the children to find while the paint dried. She ached to spend the short days and long nights of winter with a full belly and hot hearth fire, tending to murals of wildflowers and memorials so carefully that the colors never faded. But Surrie had buried that dream years ago, on the same day she learned to hate.

Instead, now for sixteenth lengths she tracked the spatters of bright blood scattered on prim snow—fresh blood, the heart’s blood, melting thumb-sized potholes in the snow—through the labyrinth of fir trees so dark green that they were nearly black. With her pulse beating in her neck, she parted the branches of a willow and beheld the precious wild doe lying warm and still and very dead, in a halo of blood, pillowed on the saplings.

Surrie, little more than a blot of red hair in the white woods, dropped to her knees. She was going to live. With this meat, she would reverse the winter’s slow sapping of strength that had left her thin and brittle and at the brink of starvation. Trembling, Surrie pressed her forehead to the doe’s, curled her fingers behind the great soft ears, and kissed the drab fur between the large dark eyes.

“Thank you for your life,” she whispered. There were no gentle winters in Savaska, but this one had been merciless. A record seven months of snow and howling wind had forced Surrie to burn through her stockpile of game meat and firewood even as more snow piled up against the door. For the past moon and a half, she had lived hand-to-mouth, fighting to scrounge up one more mouthful, one more twig for the fire, so she wouldn’t die starved and frozen in her sleep. In her nineteen years she had never become so desperate nor so profoundly grateful as she felt now for stringy, musky venison. Another prayer of gratitude followed the doe into the afterlife.

Surrie breathed in the raw, wild odor of the deer. In the end, there was little difference between the curling edges of her carving tools and the beautiful, razored edge of her hunting knife. People died, food depleted, and fires burned into cold chaff, but her blades had not failed her yet. She unsheathed her hunting knife.

Her palm molded to the leather grip of the blade like a nestled pair of bones. She’d retooled that grip herself, years ago, when her father passed it down to her after her first bleed. Not a day had gone by without her sharpening the steel edge. The cloak she wore had been his, too, tailored to and gifted to her on her sixteenth birthday, the leather as fragrant and supple as she remembered it from the milky haze of her childhood. Sometimes she fancied she could still smell pipe smoke in the thick fur that lined the collar, hear the echo of his booming laugh.

Rowan always said she was no good at letting go.

The gleam of weak sunlight on the knife edge reminded her of the price of an absent mind. A slip of the hand with her hunting knife would split her finger or palm wide open, so she wiped her mind clean to focus. With precision borne of experience she rolled the doe to the side and sliced the belly open from breast to udder. Beautiful steam curled warm and pungent where body cavity met cold air, and she leaned over the furnace that was the doe, relishing the warmth on her cheeks like a kiss.

It was stupid, but over the furnace of the doe’s belly, warmed by the knowledge that she would eat, it was hard not to feel relief—to dream, just a little bit, about the bows she could carve, the children’s toys she could chisel and paint, and the leather she could work on the side, keeping her larder comfortably stocked with bread, dried meats, and medicine. What would it be like not to be perpetually hungry, to daub something better than watery paint on the few scraps of buckskin too stiff to work into garment patches?

Sticks. Stiffened animal skin. That was the closest she came to paradise, now that she was alone.

She snapped back to reality. She had a deer to butcher, a life to honor. And what an honor it was. Even if she sold half the meat, she’d eat well for a month at least. Two good meals a day, wolf spirit be praised! Half a tenderloin would pay for soaps, and the backstrap would suffice for the moon’s taxes; a leg steak for wool, another for cloth and yarn and mortar, and the rest—

A branch snapped.

Surrie’s eyes flashed. Panther? No—too loud. Moose? No—too quiet. A brown bear, wakened by the spring sun? She shifted. A wayward wolf or two she could run off, but a bear…

Her left hand reached for the leather grip of her bow and her right nocked an arrow on the bowstring with a familiar woody click. She would sooner challenge a grizzly than choke down more mouse broth. Wolf spirit, let the intruder be benign—a very noisy squirrel, or better, another deer—

Then she marked it: the low hum of voices.

Human voices.

Oh, fuck.

Her body seized up. Her breath froze, searing, in the airways of her lungs, the many vertebrae of her spine fusing into a fragile pillar. Her stomach swooped like a great bird of prey. Her heart skipped; her palms lined themselves with sweat; then she forced her body low and pulled the hood of her cloak over the red hair that stood out like a brushfire.

Forcing herself to breathe evenly, she peered over the belly of the deer.

And there they were: some twenty-five horselengths off, half-hidden by the drooping boughs of the evergreens, two men on black horses riding down a trail. Through a break in the trees Surrie spied their cloaks, black as pooled ink and studded with cold silver. An icy stone dropped into her stomach.

Living Shadows.

Her underarms tingled as panic spurred blood down her veins to her fingertips. The Living Shadows were supposed to be holed up in Inverisk, ingratiating themselves with whatever good-for-nothing swotty lord deigned to visit. She, like the rest of the village, had been forbidden from hunting during the lord’s stay—but the Living Shadows prohibited hunting so often and with such thoughtlessness that she didn’t balk at the crime of poaching, not when the alternative was to waste into a skeleton. She received no life-saving bread or meat upon the lord’s visit, so into the woods she went, a poacher by necessity.

She knew the risks. She’d paid the heavy toll before.

Nauseous with dread, she pressed herself into the hard ice packed at the bottom of the snow, willing the scouts to miss the riotous drops of red blood on the snow and overlook her footprints stamped so clearly into the white. When she was fifteen, the Living Shadows left her back blotched with bruises the size of paving stones after catching her with a poached fox. The phantom ache rippled down her spine as she watched the two Living Shadows pass a cluster of aspens. Earlier, at thirteen, it had been ten lashes with the bullwhip. These six years later she still fancied she saw angry red weals raised parallel to her spine.

Her stomach constricted as if squeezed by some giant snake. Lordly visit or not, she had been a fool to presume the woods safe, much less to gut her salvation so close to a trail.

But there was bread to buy, clothes to mend, and cracks in the walls of her croft to mortar up, to say nothing of the perpetual hunger that gnashed like rodent teeth. She had no choice except to risk the Living Shadows’ wrath, as much as she hated to gamble.

Seconds stretched into eternity as she spied the Living Shadows from her hide. If they caught her, would it be the many-tailed whip, or the burning knife? A beating by their thugs? For one wild, unimaginable second, her right hand twitched toward her bow as if to load an arrow of its own accord. She quickly balled that rebellious hand into a useless fist. To shoot a Living Shadow, the masters of the kingdom, was answerable only with execution.

Wolf spirit, if only she could.

Fantasizing about murder, Surrie watched the Living Shadows follow the trail deeper and disappear into the bowels of the woods. Good riddance. She breathed with dizzy relief.

Safe.

Until they made another pass.

![I was blindsided by [redacted] twist, I am SHOOK. I gasped. In hindsight it was perfect.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/67eb3f2b83d156106e8d4926/1743548122662-85TV3AHA38N0KOAH19GL/unsplash-image-P8LZaU52NME.jpg)